Today I’m learning the implementation of java.util.HashMap in Java. Here’re

some study notes. The source code I’m reading is on Open JDK 11.

Constants

The default initial capacity is initialized as follows.

/**

* The default initial capacity - MUST be a power of two.

*/

static final int DEFAULT_INITIAL_CAPACITY = 1 << 4; // aka 16

The Java programming language provides operators that perform bitwise and bit shift operations on integral types. The signed left shift operator “<<” shifts a bit pattern to the left. So the expression above shifts a bit pattern 4 times:

| Bit Pattern | Integer Value | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 00000001 | 1 | 2^0 |

| 00000010 | 2 | 2^1 |

| 00000100 | 4 | 2^2 |

| 00001000 | 8 | 2^3 |

| 00010000 | 16 | 2^4 |

Storage

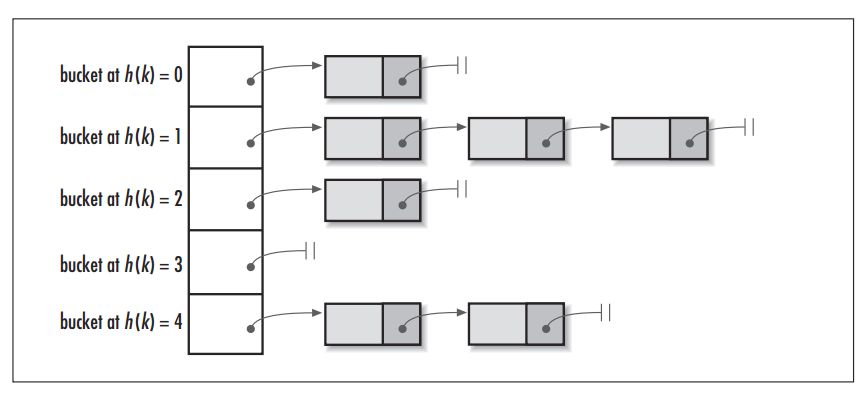

Key-value pairs are stored in a table. This table is

initialized on first use, and resized as necessary. When allocated, length is

always a power of two. The table is accessible via hash value of the key K.

The keyword “transient” is declared, because as a class member, table is

unnecessary to reconstruct the object from its serialized form.

transient Node<K,V>[] table;

Here’s a figure illustrating the internal table structure:

Hash

Compute the key’s hash, which is used to calculate the index of in array

(table). This is the core function in the HashMap. When the key is null, the

hash code is set to 0; else, it is computed using key’s hash code

(key.hashCode()) and spreading (XOR) higher bits of hash to lower.

static final int hash(Object key) {

int h;

return (key == null) ? 0 : (h = key.hashCode()) ^ (h >>> 16);

}

To better illustrate the changes of int h, I created the following table,

where hash code is set to 0xffffffff. As you can see, the shift operation

h >>> 16 is a transformation that spreads the impact of hight bits downward

(bits >= positions 16th):

| Operation | Binary Value |

|---|---|

h = key.hashCode() |

1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 |

h >>> 16 |

0000 0000 0000 0000 1111 1111 1111 1111 |

h ^ (h >>> 16) |

1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 |

But why we need h >>> 16? Because shifting the bits allows the highest bits

to participate into index calculations. Combined with the XOR operation

h ^ (h >>> 16), it is the cheapest possible way to do it. Here’s the

Javadoc in Java 11:

…, we just XOR some shifted bits in the cheapest possible way to reduce systematic lossage, as well as to incorporate impact of the highest bits that would otherwise never be used in index calculations because of table bounds.

You might still be confused about the hash function and its benefits. Don’t worry, let’s pause the question and see how the index calculation works. We will review the hash function afterward.

Index Calculation

Map the hash code to an index in the array. In the simplest way, this could be

done by performing a modulo operation on hash code and length of array, such as

hash(key) % n. Why not using hash as the index directly? Because hash

might be greater than the size of range, thus index out of bound. Using modulo

ensures that index i is always between 0 and n.

i = hash % n;

In the real Java HashMap implementation, it is something different. Index i

is calculated by the following expression:

i = (n - 1) & hash;

In this expression, variable n refers to the length of the table, and hash

refers to the hash of the key. This is a simplification of the modulo operation

using bit operation. In Java HashMap, the length of the table is always a power

of two (2^x), it means that modulo operation by a bitwise AND (&).

This can be done because n is always a power of two, thus n - 1 is always a

bit pattern having 1 at each position. In other words, n - 1 is a mask for

finding the reminder. A concrete example is as follows with table size n = 4,

hash values [0, 5], and two calculations equivalent:

| n | hash | hash % n | (n - 1) & hash |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0 | 0 % 4 = 0 | 0 & 3 = 000 & 011 = 000 = 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 % 4 = 1 | 1 & 3 = 001 & 011 = 001 = 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 % 4 = 2 | 2 & 3 = 010 & 011 = 010 = 2 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 % 4 = 3 | 3 & 3 = 011 & 011 = 011 = 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 % 4 = 0 | 4 & 3 = 100 & 011 = 000 = 0 |

| 4 | 5 | 5 % 4 = 1 | 5 & 3 = 101 & 011 = 001 = 1 |

Now, we understand index calculation is done using modulo. Let’s go back to the

hash calculation hash(Object), to review the expression h ^ (h >>> 16).

Since we calculate the modulo using a bit mask ((n - 1) & hash), any bit

higher than highest bit of n - 1 will not be used by the modulo. For example,

given n = 32 and 4 hash codes to calculate. When doing the modulo directly

without hash code transformation, all indexes will be 1. The collision is 100%.

This is because mask 31 (n - 1), 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001 1111,

makes any bit higher than position 5 un-usable in number h. In order to use

these highest bits, HashMap shifts them 16 positions left h >>> 16 and

spreads with lowest bits (h ^ (h >>> 16)). As a result, the modulo obtained

has less collision.

| h | h (binary) | h % 32 | (h ^ h >>> 16) % 32 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65,537 | 0000 0000 0000 0001 0000 0000 0000 0001 | 1 | 0 |

| 131,073 | 0000 0000 0000 0010 0000 0000 0000 0001 | 1 | 3 |

| 262,145 | 0000 0000 0000 0100 0000 0000 0000 0001 | 1 | 5 |

| 524,289 | 0000 0000 0000 1000 0000 0000 0000 0001 | 1 | 1 |

Put Operation

What happens when a new entry (key-value pair) is put into the HashMap?

According to the Javadoc of method #put(K key, V value), it associates

the specified value with the specified key in this map. If the map previously

contained a mapping for the key, the old value is replaced.

public V put(K key, V value) {

return putVal(hash(key), key, value, false, true);

}

The internal operation putValue takes 5 arguments:

int hash: the hash value for the key, computed by the utility method hash().K key: the key to putV value: the value to putboolean onlyIfAbsent: decision about changing the existing value or not. Here, it is set to false, so the if the key is present, the existing value will be overwritten.boolean evict: if false, the table is in creation mode. Here true, so the table is not in creation mode.

Now take a look into the putValue method. Firstly, it does a validation on the

node table. If the table does not exist or its length is 0, then the table will

be resized; Then, it checks if value exists in the target index: if not exist,

construct a new node and insert to table, else handle it in a more complex way.

Node<K,V>[] tab; Node<K,V> p; int n, i;

if ((tab = table) == null || (n = tab.length) == 0)

n = (tab = resize()).length;

if ((p = tab[i = (n - 1) & hash]) == null)

tab[i] = newNode(hash, key, value, null);

else {

...

}

In the previous section, we already saw that target index is determined using

expression (n - 1) & hash, and that HashMap creates a new entry when the

target index is empty. In

the following paragraph, let’s take a look how it replace an existing mapping

for key.

If mapping exists at target index, there’re 3 cases:

- the bucket matches the target key (regular node)

- the bucket does not match the target key, and it is a tree node

- the bucket does not match the target key, and it is not a tree node

In the first case, implementation tests 2 conditions: the previous hash value

must be the same as the current one; the previous key is the same as, or is

equals to the current key. Note that there’s a delayed assignment for variable

k, because it might not need to be assigned—when the hash values are

different.

Node<K,V> e; K k;

if (p.hash == hash &&

((k = p.key) == key || (key != null && key.equals(k))))

e = p;

In the second case, implementation checks if p is a TreeNode. If it is, then put the value into the tree. This is an improvement done in Java 8 coming from JEP 180: Handle Frequent HashMap Collisions with Balanced Trees. The principal idea is that once the number of items in a hash bucket grows beyond a certain threshold, that bucket will switch from using a linked list of entries to a balanced tree. In the case of high hash collisions, this will improve worst-case performance from O(n) to O(log n).

else if (p instanceof TreeNode)

e = ((TreeNode<K,V>)p).putTreeVal(this, tab, hash, key, value);

In the third case, implementation considers the bucket as a linked list. It iterates all the bins, and acts according to different cases: 1. skip the lookup if the target key is found; 2. add a new node at the end of list if the target key is not found; 3. transform the list into a tree if the threshold is reached.

for (int binCount = 0; ; ++binCount) {

if ((e = p.next) == null) {

p.next = newNode(hash, key, value, null);

if (binCount >= TREEIFY_THRESHOLD - 1) // -1 for 1st

treeifyBin(tab, hash);

break;

}

if (e.hash == hash &&

((k = e.key) == key || (key != null && key.equals(k))))

break;

p = e;

}

In the previous operations, the existing mapping for key k is stored as

Node<K,V> e. If not null, it means that a mapping has been found.

Therefore, replace entry e’s old value by the new one, then return the old

value. (Note that method afterNodeAccess is an empty method in HashMap—it is a

callback to allow LinkedHashMap post-actions.)

if (e != null) { // existing mapping for key

V oldValue = e.value;

if (!onlyIfAbsent || oldValue == null)

e.value = value;

afterNodeAccess(e);

return oldValue;

}

Now the replacement operation is finished. But still another case to

consider—when the put operation is not a replacement. If not a replacement, then

we’re modifying the HashMap’s structure. Implementation records the number of

modifications via modCount and the number of entries stored in the HashMap via

size. Transient integer modCount is the number of times this HashMap has

been structurally modified, used to make iterators on Collection-views of the

HashMap fail-fast; transient integer size is the number of key-value mappings

contained in this map, used to determine when the map should be resized. (Note

that method afterNodeInsertion is an empty method an HashMap—it is a callback

to allow LinkedHashMap post-actions.)

++modCount;

if (++size > threshold)

resize();

afterNodeInsertion(evict);

return null;

References

- Gayle Laakmann Mcdowell, “Chapter 1 Arrays and Strings - Hash Tables”, Cracking The Coding Interview 6th Edition, 2019. [Book]

- harold, “Why HashMap insert new Node on index (n - 1) & hash?”, Stack Overflow, 2014. https://stackoverflow.com/a/27231004

- Aniket Thakur, “Why HashMap insert new Node on index (n - 1) & hash?”, Stack Overflow, 2018. https://stackoverflow.com/a/44615382

- Stephen C, “Change to HashMap hash function in Java 8”, Stack Overflow, 2014. https://stackoverflow.com/a/24676184

- philwb, “Understanding strange Java hash function”, Stack Overflow, 2012. https://stackoverflow.com/a/9336515

- Oracle, “Collections Framework Enhancements in Java SE 8”, Oracle Java Documentation, 2018. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/technotes/guides/collections/changes8.html

- Mike Duigou, “JEP 180: Handle Frequent HashMap Collisions with Balanced Trees”, Open JDK, 2017. http://openjdk.java.net/jeps/180

- ITCuties, “HashMap vs. Hashtable”, ITCuties, 2014. http://www.itcuties.com/java/hashmap-hashtable/

- Felix, “hashCode() 和 hash 算法的那些事儿”, Flix’s Blog, 2018. https://yfzhou.coding.me/2018/12/06/hashCode-%E5%92%8Chash%E7%AE%97%E6%B3%95%E7%9A%84%E9%82%A3%E4%BA%9B%E4%BA%8B%E5%84%BF/