Introduction

During my daily work at Datadog, I had the chance to use the GitLab Go API client (xanzy/go-gitlab) to interact with our GitLab server. I feel that the library is well written and I want to learn how to write a library in the same way. That’s why I spent some time studying its source code and I would like to share it with you today. After reading this article, you will understand:

- How to use this package

- The structure of the Go package

- The HTTP request and response

- Its dependencies

- The CI pipeline

- Its advanced features

- Publishing the documentation

Now, let’s get started!

Usage

Using the GitLab library is very simple, you need to create a new client with a token and then use the domain-specific sub-client to access certain resources. For example, this is the code for listing users, provided by the official documentation:

import "github.com/xanzy/go-gitlab"

// ...

git, err := gitlab.NewClient("yourtokengoeshere")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to create client: %v", err)

}

users, _, err := git.Users.ListUsers(&gitlab.ListUsersOptions{})

There are a few With... option functions that can be used to customize the API

client. For example, to set a custom base URL:

git, err := gitlab.NewClient("yourtokengoeshere", gitlab.WithBaseURL("https://git.mydomain.com/api/v4"))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to create client: %v", err)

}

users, _, err := git.Users.ListUsers(&gitlab.ListUsersOptions{})

We will discuss this more in detail in the following sections.

Package Structure

The structure of this package is pretty simple, most of the files are located

directly in the root directory of the Git repository. The Go files are grouped

by domain: each domain has 2 files, one for the source code and the other for

the test code, e.g. access_requests.go and access_requests_test.go.

➜ go-gitlab git:(master|u=) tree | head

.

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── access_requests.go

├── access_requests_test.go

├── applications.go

├── applications_test.go

├── audit_events.go

├── audit_events_test.go

├── avatar.go

Inside each domain, we can find multiple things: the sub-client of this domain; the Go structures

representing the HTTP requests and responses for this domain; and

the related methods. For example, for the domain “jobs”

(jobs.go), we can find the JobsService which is the client of the domain

“jobs”; we can find the structures: Job and Bridge; we

can also see the methods for different purposes: listing project jobs, listing

pipeline jobs, listing pipeline bridges, etc.

// JobsService handles communication with the ci builds related methods

// of the GitLab API.

//

// GitLab API docs: https://docs.gitlab.com/ce/api/jobs.html

type JobsService struct {

client *Client

}

type Job struct {

Commit *Commit `json:"commit"`

Coverage float64 `json:"coverage"`

// ...

}

type Bridge struct {

Commit *Commit `json:"commit"`

Coverage float64 `json:"coverage"`

// ...

}

// ...

func (s *JobsService) ListProjectJobs(...) ([]*Job, *Response, error) { ... }

Then, if you want to go further into the HTTP request handling, you will find

out that the actual preparation of the request is not handled by the domain.

It’s delegated to the underlying *Client, which is a low-level HTTP client

shared by all the domains. Internally, it marshals the Go structure into an HTTP

request, sends the request, waits for the HTTP response, unmarshals it back to

Go structure, and handle eventual errors. To better understand the relationship

between the domain-specific client and the low-level HTTP client, let’s draw a

diagram

(excalidraw):

This structure uses the delegation pattern (wikipedia), which allows reusing the same logic for every domain. Therefore, you don’t have to repeat yourself. It’s pretty cool, isn’t it?

However, this requires some work. During the initialization of the GitLab Go

client, you need to initialize the low-level client and the high-level clients

correctly as shown below. Inside the gitlab.go file, we can see that a new structure is

created for each public service (domain), and the low-level client is wired to

the current client c. Without it, the service (domain) cannot handle the HTTP

request correctly.

// file: gitlab.go

func newClient(options ...ClientOptionFunc) (*Client, error) {

c := &Client{UserAgent: userAgent}

// Configure the HTTP client.

// ...

// Create all the public services.

c.AccessRequests = &AccessRequestsService{client: c}

c.Applications = &ApplicationsService{client: c}

c.AuditEvents = &AuditEventsService{client: c}

c.Avatar = &AvatarRequestsService{client: c}

c.AwardEmoji = &AwardEmojiService{client: c}

Request and Response

Thanks to the section above, we have a better overview of the package structure. However, it’s still not clear how the SDK handles an HTTP request for us. In this section, we are going to discuss it. More precisely, we will use the “List Project Jobs API” as an example to learn the internal mechanism and get the exact sequence of the related actions.

Before listing the jobs, you need to instantiate a new GitLab client via the

method NewClient(...). Once it is created, you can list the jobs of a given

project. This is done by invoking the sub-client client.Jobs, which represents the

job service of GitLab. This service uses the ListProjectJobs to achieve the

goal. Internally, it delegates the logic to the low-level client *Client to

perform the HTTP request. The low-level client sets up the headers, marchals the

input Go structure into JSON, then delegates again the actual request to HashiCorp

Retryable HTTP, a third-party library. This library interacts with the GitLab

server and waits for the HTTP response to be returned. Once done, it returns

either the correct response or the error to the upper levels. At the job service

level, if it receives the correct response, it will unmarshal it back to a Go

structure []*Job before returning it to the user.

sequenceDiagram

Caller->>GitLab Client: New Client

GitLab Client-->>Caller: Client

Caller->>Job Service: List Project Jobs

Job Service->>GitLab Client: New Request

GitLab Client->>HashiCorp Retryable HTTP: New Request

HashiCorp Retryable HTTP->>GitLab: Request

GitLab-->>HashiCorp Retryable HTTP: Raw Response, Error

HashiCorp Retryable HTTP-->>GitLab Client: Raw Response, Error

GitLab Client-->>Job Service: Raw Response, Error

Job Service-->>Caller: Jobs, Raw Response, Error

Now, let’s go further into marshaling and unmarshaling. Marshalling happens

when preparing the HTTP request and unmarshaling happens when receiving the

HTTP response. The marshaling process transforms the Go structure into JSON.

For listing the project’s jobs, the related Go structure is ListJobsOptions.

// file: jobs.go

// ListJobsOptions represents the available ListProjectJobs() options.

//

// GitLab API docs:

// https://docs.gitlab.com/ce/api/jobs.html#list-project-jobs

type ListJobsOptions struct {

ListOptions

Scope *[]BuildStateValue `url:"scope[],omitempty" json:"scope,omitempty"`

IncludeRetried *bool `url:"include_retried,omitempty" json:"include_retried,omitempty"`

}

The marshaling happens inside the low-level client, where the function

NewRequest accepts whatever input option as an interface, and marshals it as the

request body. This is handled by the built-in package “encoding/json” in Go. The

function also sets the media type as “application/json” to let the server knows

the type of content.

// file: gitlab.go

import (

"bytes"

"context"

"encoding/json"

// ...

)

func (c *Client) NewRequest(method, path string, opt interface{}, options []RequestOptionFunc) (*retryablehttp.Request, error) {

//...

var body interface{}

switch {

case method == http.MethodPost || method == http.MethodPut:

reqHeaders.Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

if opt != nil {

body, err = json.Marshal(opt)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

Once the response is received by the client, the unmarshaling process starts.

More precisely, it is initialized in the domain-level client but handled by the

low-level client. Let’s take “list project jobs” as an example, the jobs service

declares the variable var job []*Job without assigning the variable. This

reference of this variable is passed to the low-level s.client. Inside the

low-level client,

it uses the built-in Go package “encoding/json” to unmarshal the HTTP response.

Note that this variable v is not returned as part of the function output, because

the assignment happens in place. That is, when we decode the variable v, the

caller already has access to this information because both the low-level client

and the caller point to the same reference of *ListJobsOptions. You may notice

that the GitLab client also supports I/O stream, which is useful for downloading

resources, such as downloading the artifacts of a job.

// file: jobs.go

func (s *JobsService) ListProjectJobs(pid interface{}, opts *ListJobsOptions, options ...RequestOptionFunc) ([]*Job, *Response, error) {

// ...

var jobs []*Job

resp, err := s.client.Do(req, &jobs)

if err != nil {

return nil, resp, err

}

// file: gitlab.go

func (c *Client) Do(req *retryablehttp.Request, v interface{}) (*Response, error) {

// ...

if v != nil {

if w, ok := v.(io.Writer); ok {

_, err = io.Copy(w, resp.Body)

} else {

err = json.NewDecoder(resp.Body).Decode(v)

}

}

return response, err

}

Error Handling

Error handling is an important part of any SDK. In this section, we are going to discuss how GitLab SDK handles errors. In general, there are two types of errors: non-API errors and API errors. Non-API errors are errors that are unrelated to the GitLab APIs. This can happen before sending an HTTP request. API errors are errors that are related to the GitLab APIs. It means that the error is provided by the GitLab server with a standard error structure.

The non-API errors happen in the low-level client (gitlab.go) where we try to

prepare the HTTP request with a limiter; request an OAuth token; submit an HTTP

request; etc. As you can see, in any of the cases, we don’t have a response from

the GitLab Server. It means that the error happens before receiving the response

or even before sending the request.

// Wait will block until the limiter can obtain a new token.

err := c.limiter.Wait(req.Context())

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if basicAuthToken == "" {

// If we don't have a token yet, we first need to request one.

basicAuthToken, err = c.requestOAuthToken(req.Context(), basicAuthToken)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

req.Header.Set("Authorization", "Bearer "+basicAuthToken)

resp, err := c.client.Do(req)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

Now, let’s take a look at the API errors. API errors are representations of the failures returned by the GitLab server. This happens when the request has been successfully sent but the client received a failing response. According to the GitLab official documentation “Data validation and error reporting”, the structure of the error message can be described as follows:

{

"message": {

"<property-name>": [

"<error-message>",

"<error-message>",

...

],

"<embed-entity>": {

"<property-name>": [

"<error-message>",

"<error-message>",

...

],

}

}

}

In the GitLab client SDK, it parses the error following exactly this structure

via the function parseError(...).

If we take a step back, an API error is created in the following way. If the

HTTP response is successful or cached, it is not considered as an error. Else,

we retrieve the response body as bytes and parse it. The parsing logic is split

into 2 steps: 1) we verify if this is a valid JSON format by unmarshaling it

via the json.Unmarshal function; 2) then, we parse the fields one by one and

create a string representation of the error. Finally, the function returns a

reference of the structure *ErrorResponse, which encapsulates both the raw

HTTP response r and the string representation of the error message.

// CheckResponse checks the API response for errors, and returns them if present.

func CheckResponse(r *http.Response) error {

switch r.StatusCode {

case 200, 201, 202, 204, 304:

return nil

}

errorResponse := &ErrorResponse{Response: r}

data, err := io.ReadAll(r.Body)

if err == nil && data != nil {

errorResponse.Body = data

var raw interface{}

if err := json.Unmarshal(data, &raw); err != nil {

errorResponse.Message = fmt.Sprintf("failed to parse unknown error format: %s", data)

} else {

errorResponse.Message = parseError(raw)

}

}

return errorResponse

}

Dependency

In the previous section, we focused on one single request and studied the

sequence of the actions. Now, let’s change an angle and look at its

dependencies. Below is the go.mod file which describes the module’s

properties, including its dependencies.

module github.com/xanzy/go-gitlab

go 1.18

require (

github.com/google/go-querystring v1.1.0

github.com/hashicorp/go-cleanhttp v0.5.2

github.com/hashicorp/go-retryablehttp v0.7.1

github.com/stretchr/testify v1.8.0

golang.org/x/oauth2 v0.0.0-20220722155238-128564f6959c

golang.org/x/time v0.0.0-20220722155302-e5dcc9cfc0b9

)

require (

github.com/davecgh/go-spew v1.1.1 // indirect

github.com/golang/protobuf v1.5.2 // indirect

github.com/pmezard/go-difflib v1.0.0 // indirect

golang.org/x/net v0.0.0-20220805013720-a33c5aa5df48 // indirect

google.golang.org/appengine v1.6.7 // indirect

google.golang.org/protobuf v1.28.1 // indirect

gopkg.in/yaml.v3 v3.0.1 // indirect

)

Here is a brief analysis of each direct dependency:

github.com/google/go-querystringis used for constructing query parameters for HTTP requests. This is useful for URL encoding.github.com/hashicorp/go-cleanhttpis used for setting up the HTTP client used by the retryable http client. In particular, it sets up a connection pool for the client.github.com/hashicorp/go-retryablehttpis used for handling the retry mechansim for the http requests.github.com/stretchr/testifyis used for writing tests.golang.org/x/oauth2is used for handling open authorization (OAuth).golang.org/x/timeis used for facilitating operations related to datetime.

As for the indirect dependencies, they are dependencies used by the direct dependencies mentioned above. They are transitive dependencies. See ”//indirect for a dependency in go.mod file in Go (Golang)” to learn more about this.

CI

Continuous integration also plays an important part in the success of the project. It allows maintainers to focus on what matters and reduce the burden. This GitLab SDK uses GitHub actions to run linting and tests. It is configured to test the 3 major Go versions: 1.18, 1.19, and the latest one.

name: Lint and Test - ${{ matrix.go-version }}

strategy:

matrix:

go-version: [1.18.x, 1.19.x, 1.x]

platform: [ubuntu-latest]

runs-on: ${{ matrix.platform }}

The lint is handled by the Golang CI lint action and the tests are handled by

the built-in go test command, which traverses the repository recursively with

coverage measurement enabled.

- name: Test package

run: |

go test -v ./... -coverprofile=coverage.txt -covermode count

go tool cover -func coverage.txt

Advanced Features

The GitLab Go SDK also contains some advanced features that we didn’t have a chance to discuss so far, such as its retry mechanism, pagination, and its option functions. Here, I want to briefly talk about them.

Retry mechanism. According to HashiCorp’s official

documentation, “the

retryable package provides a familiar HTTP client interface with automatic

retries and exponential backoff. It’s a thin wrapper over the standard

net/http client library and exposes nearly the same public API. This makes

retryablehttp very easy to drop into existing programs.”. The retry mechanism

is triggered automatically under certain conditions, such as when a connection

error occurred, or a 500-range response is received (except 501 Not Implemented).

Some of the configurations are exposed as a client option function, where you can

customize your GitLab client as you want. Below, you can see an example that

allows you to configure a custom backoff policy:

// file: client_options.go

// WithCustomBackoff can be used to configure a custom backoff policy.

func WithCustomBackoff(backoff retryablehttp.Backoff) ClientOptionFunc {

return func(c *Client) error {

c.client.Backoff = backoff

return nil

}

}

There are also options to configure the maximum number of retries, the retry policy, the logger, etc.

Pagination. GitLab supports two types of pagination methods: offset-based

pagination and keyset-based pagination

(documentation). The offset-based

pagination is supported by the GitLab API Go client. This is achieved by two

pieces of code: the listing options in the request and the pagination-related

info in the response. More precisely, when listing some resources, you can

specify the offset and the limit of your pagination via the ListOptions

structure using variables “Page” and “PerPage”. When returning the HTTP response,

the SDK uses a wrapper structure around the built-in HTTP response to contain

the information related to pagination.

// file: gitlab.go

// ListOptions specifies the optional parameters to various List methods that

// support pagination.

type ListOptions struct {

// For paginated result sets, page of results to retrieve.

Page int `url:"page,omitempty" json:"page,omitempty"`

// For paginated result sets, the number of results to include per page.

PerPage int `url:"per_page,omitempty" json:"per_page,omitempty"`

}

// ...

// Response is a GitLab API response. This wraps the standard http.Response

// returned from GitLab and provides convenient access to things like

// pagination links.

type Response struct {

*http.Response

// These fields provide the page values for paginating through a set of

// results. Any or all of these may be set to the zero value for

// responses that are not part of a paginated set, or for which there

// are no additional pages.

TotalItems int

TotalPages int

ItemsPerPage int

CurrentPage int

NextPage int

PreviousPage int

}

But isn’t the response being transformed into the actual Go structure before returning to the caller? Well, actually both of them are returned: not only the actual Go structure but also the wrapped HTTP response. Below, you can see an example from “listing project jobs”:

func (s *JobsService) ListProjectJobs(

pid interface{},

opts *ListJobsOptions,

options ...RequestOptionFunc) ([]*Job, *Response, error) { ... }

Option Functions. The GitLab SDK provides some With... option functions to

let you customize the API client. Why? Because the default values may not fit

100% of your need and you want to do something differently. This notion is

probably introduced by Dave Cheney in his post “Functional options for friendly

APIs”

back to 2014. The main benefits of using functional options are: letting you

write beautiful APIs that can grow over time; enabling the default use case to be

its simplest; giving more readable and meaningful parameters; and providing direct

control over the initialization of complex values.

The GitLab API client provides options to set the base URL, configure backoff policy, logging, error handling, HTTP client, etc.

git, err := gitlab.NewClient("yourtokengoeshere", gitlab.WithBaseURL("https://git.mydomain.com/api/v4"))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to create client: %v", err)

}

users, _, err := git.Users.ListUsers(&gitlab.ListUsersOptions{})

Using the With... style functions to configure options is common in Go. You

can see similar patterns in gRPC when creating a client connection to the given

target (doc). For example:

conn, err := grpc.Dial(addr,

grpc.WithTransportCredentials(insecure.NewCredentials()),

grpc.WithChainUnaryInterceptor(myInterceptor),

// ...

)

Or simply changing the context using the builtin context library to inject new

key value pair, setting timeout, etc as mentioned by Kshitij Kumar in his

article “Notes: Golang Context”:

ctx := context.WithValue(context.Background(), "my_key", "my_value")

// context with deadline after 2 millisecond

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 2*time.Millisecond)

Documentation

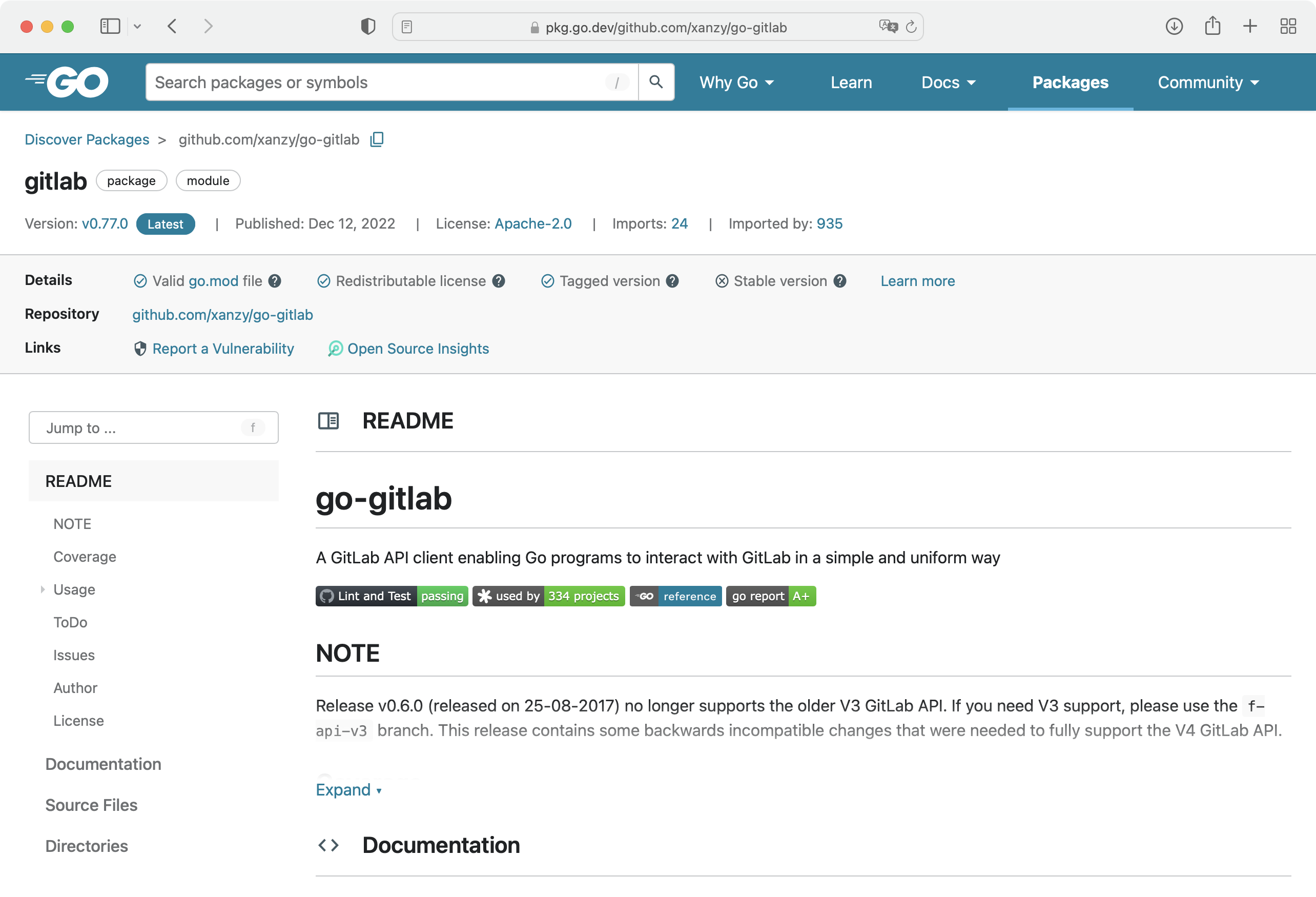

As many other open-source projects written in Go, the documentation of this SDK is published to Go package repository under https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/xanzy/go-gitlab.

The documentation is probably published manually to the Go package repository because I don’t see integration in the CI. It should be very simple, the Go official website has instructions about the publishing process here.

Conclusion

In this article, we went into the implementation of the GitLab API Go client and learned about different aspects of this library, including the package structure, the request and response, the error handling, its dependency, the CI pipeline, its advanced features (retry mechanism, pagination, client options), and its documentation. I hope that it gives a better understanding of this library, gives you ideas for troubleshooting, or inspires you to write your SDK! Interested to know more? You can subscribe to the feed of my blog, follow me on Twitter or GitHub. Hope you enjoy this article, see you the next time!

P.S. Special thanks to Giorgos Georgiou for reviewing this post.