Introduction

In the last months, I wrote many articles explaining how to use solve one specific problem in software. But I start to get tired of it and would like to try something new: something that is based on a project. Today, I will start a new series about Elasticsearch documenting my new personal project: DVF. Open data “Demande de valeurs foncières (DVF)” is an open dataset provided by the French government which collects all the real-estate transactions since January 2014, in mainland France and the overseas departments and territories, except in Mayotte and Alsace-Moselle.

This blog series will focus on the features of Elasticsearch by using the DVF dataset. We are going to explore how to index documents, optimize storage, backup, and search documents using Elasticsearch. The main technologies used in this series are: Elasticsearch, Docker, Java, and Postman.

This article will only cover the first part: indexing. We are going to see how to download the dataset, prepare the environment, set up index mappings, and create new documents in Elasticsearch. After reading this article, you will understand:

- How to download the dataset?

- How to read the dataset? (deserialization)

- How to set up Elasticsearch using Docker?

- How to set up Java High Level REST Client?

- How to create a new index and handle mappings?

- How to create new documents?

Now, let’s get started!

Download Dataset

You can download the dataset from https://cadastre.data.gouv.fr/dvf, where the

dataset is separated per year: 2014, 2015, 2016… There are two format: TXT and

CSV format. The one chosen here is the CSV one. You can find them here:

https://cadastre.data.gouv.fr/data/etalab-dvf/latest/csv/. Once downloaded,

you will get a compressed file called “full.csv.gz”. Depending on the chosen year, it will

contain the dataset of that year. For example, the “full.csv.gz” of 2020

contains all the transactions of 2020. You may want to rename it to avoid

conflictions if you want to download multiple years. Then, you need to

uncompress the file to obtain the CSV file. I use the gunzip command to handle

it:

gunzip full.csv.gz

… and a CSV file called full.csv without the .gz will be available in the

same directory. Here is how the CSV of year 2020 looks like by showing the top 3

lines (head -n 3 full.csv):

id_mutation,date_mutation,numero_disposition,nature_mutation,valeur_fonciere,adresse_numero,adresse_suffixe,adresse_nom_voie,adresse_code_voie,code_postal,code_commune,nom_commune,code_departement,ancien_code_commune,ancien_nom_commune,id_parcelle,ancien_id_parcelle,numero_volume,lot1_numero,lot1_surface_carrez,lot2_numero,lot2_surface_carrez,lot3_numero,lot3_surface_carrez,lot4_numero,lot4_surface_carrez,lot5_numero,lot5_surface_carrez,nombre_lots,code_type_local,type_local,surface_reelle_bati,nombre_pieces_principales,code_nature_culture,nature_culture,code_nature_culture_speciale,nature_culture_speciale,surface_terrain,longitude,latitude

2020-1,2020-01-07,000001,Vente,8000,,,FORTUNAT,B063,01250,01072,Ceyzériat,01,,,01072000AK0216,,,,,,,,,,,,,0,,,,,T,terres,,,1061,5.323522,46.171899

2020-2,2020-01-07,000001,Vente,75000,,,RUE DE LA CHARTREUSE,0064,01960,01289,Péronnas,01,,,01289000AI0210,,,,,,,,,,,,,0,,,,,AB,terrains a bâtir,,,610,5.226197,46.184538

As you can see, there are a lot of columns here. The mappings will be fun… But we are going to cover that later. Before going further, let’s measure the size of the dataset: this CSV file is 136MB and contains 827,106 transactions from January 2020 to June 2020.

$ du -h full.2020.csv

136M full.2020.csv

$ wc -l full.2020.csv

827106 full.2020.csv

Read Dataset

To read the CSV file, I chose the framework Jackson because Jackson is one of

the most popular frameworks about JSON serialization in the Java ecosystem.

Here, we are using the module Jackson Data-Format CSV (jackson-dataformat-csv)

to deserialize from the CSV file. Since this article is more about Elasticsearch, I

try to be short about CSV handling. Briefly speaking, we need the

following things to read CSV rows:

- Create a Jackson

CsvSchemato be used during deserialization - Create a Jackson

CsvMapperto deserialize the CSV.CsvMapperinherits the famous JacksonObjectMapper. - Create a value class

TransactionRowto represent a row in the CSV file. This class contains the@JsonPropertyannotations used for the JSON/Java mapping and@JsonPropertyOrderannotation used for specifying the order of the column in the CSV file. If we don’t specify@JsonPropertyOrder, the alphabetic order of the columns will be used, which will make the deserialization wrong. For this value class, I use framework Immutables to generate the class.

Here is the key logic for creating a new CSV mapper, a new CSV schema, and a new object reader to read the values from the csv file:

var csvMapper = Jackson.newCsvMapper();

var csvSchema = csvMapper.schemaFor(TransactionRow.class).withHeader();

var objectReader = csvMapper.readerFor(TransactionRow.class).with(csvSchema);

Iterator<ImmutableTransactionRow> iterator = objectReader.readValues(csv);

And the class of TransactionRow:

@Immutable

@JsonSerialize(as = ImmutableTransactionRow.class)

@JsonDeserialize(as = ImmutableTransactionRow.class)

@JsonPropertyOrder({

"id_mutation",

"date_mutation",

"numero_disposition",

...

})

public interface TransactionRow {

@JsonProperty("id_mutation")

String mutationId();

@JsonProperty("date_mutation")

LocalDate mutationDate();

@JsonProperty("numero_disposition")

String dispositionNumber();

...

}

The implementation of the transaction row is handled by Immutables. More precisely,

it is generated by the annotation processor of Immutables during code

compilation. The generated version is called ImmutableTransactionRow. As the

name suggested.

Why using Iterator instead of List?

As you may have observed, the object reader does not return all the values from the

CSV as a list. Why? This is because the CSV is too big, returning a list of

transactions eagerly can trigger a java.lang.OutOfMemoryError. This was the

case when I wrote the first version of the implementation. Here, using an iterator

means returning the transactions lazily, only deserialize the target row when

next() is called.

Iterator<ImmutableTransactionRow> iterator = objectReader.readValues(csv);

We can also convert this iterator into a Java stream using the helper class

StreamSupport:

Iterator<ImmutableTransactionRow> iterator = objectReader.readValues(csv);

Stream<ImmutableTransactionRow> stream = StreamSupport.stream(

Spliterators.spliteratorUnknownSize(iterator, ORDERED),

false

);

At this point, we can consider that the dataset is prepared and we can start preparing the Elasticsearch server and Elasticsearch client.

Set Up Elasticsearch

The easiest way to set up Elasticsearch is via Docker. Elasticsearch provides an official Docker image elasticsearch and provides a detailed installation guide here: Install Elasticsearch with Docker. You can start multiple nodes with Docker Compose to create a cluster or you can start a single node for development or testing. In our case, we are going to use the single-node mode, which requires less CPU and less memory. This is because I’m running Elasticsearch in my Macbook Pro 2015 with 2.7 GHz Dual-Core Intel Core i5 and 8 GB 1867 MHz DDR3, which is not super performant. Before starting the Docker image, we also need to prepare a Docker volume so that the documents indexed will persist even if we shut down the Docker container. Here is the command that I use to start the Docker:

esdata="${HOME}/dvf-volume-es"

docker run \

--rm \

-p 9200:9200 \

-p 9300:9300 \

-e "discovery.type=single-node" \

-e "cluster.name=es-docker-cluster" \

-v "$esdata":/usr/share/elasticsearch/data \

docker.elastic.co/elasticsearch/elasticsearch:7.10.1

From the command above, you can see that the Docker volume for Elasticsearch is

located in my local hard disk at path ~/dvf-volume-es and it’s mounted to

/usr/share/elasticsearch/data which is the common location to store the

Elasticsearch data inside a Docker container. The Docker container will be

removed once the container is stopped because we specified the option --rm.

We bind the port 9200 and port 9300 of the container to TCP port 9200 and

9300 on localhost. We also specified the environment variable

discovery.type=single-node to ensure that Elasticsearch is started as a

single-node cluster and will bypass the bootstrap checks. We specified the

cluster name as es-docker-cluster. We mounted the volume to persist data as

explained above. And finally, we used the image elasticsearch of version

7.10.1 from the registry of Elasticsearch (https://docker.elastic.co).

This version is the latest at

the time I write this article. This command starts the Docker container in the

foreground so you can stop the container any time you want by pressing keys CTRL + C.

Set Up Java Client

Transport Client or Java High Level REST Client?

In the section above, we finished the set up on the server side (Elasticsearch). Now, let’s continue on the client side. In this article, I am using the Java client because Java is the best programming language in the world 😝 If you were familiar with Elasticsearch, you probably know that there are two Java clients in Elasticsearch: the Transport Client and the Java High Level REST Client. The reason I chose REST Client is that the Transport Client is deprecated in favor of the REST client and will be removed in Elasticsearch 8.0. The new client is better because the Transport Client uses the transport protocol to communicate with Elasticsearch, which causes compatibility problems if the client is not on the same version as the Elasticsearch instances it talks to.

To set up the Java High Level REST Client, you need to download the following dependency if you are using Maven:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.elasticsearch.client</groupId>

<artifactId>elasticsearch-rest-high-level-client</artifactId>

<version>7.10.1</version>

</dependency>

And then set up the Java client:

var builder = RestClient.builder(new HttpHost("localhost", 9200, "http"));

try (var restClient = new RestHighLevelClient(builder)) {

// TODO: implementation goes here

}

Elasticsearch Mappings

What are index mappings in Elasticsearch?

According to official documentation “Mapping (7.x)”, mapping is the process of defining how a document, and the fields it contains, are stored and indexed. For instance, use mappings to define which string fields should be treated as full-text fields; which fields contain numbers, dates, or geolocations; the format of the date values; custom rules to control the mappings for dynamically added fields.

There are two types of mapping modes: dynamic mappings or explicit mappings. When using dynamic mappings, fields and mapping types do not need to be defined before being used, new field names will be added automatically. The other mode is explicit mappings, where we can create the field mappings when creating a new index. Explicit mappings are the mode that we use in this article because the type of each field is well known. Making Elasticsearch guess the types can make them incorrect.

Which data types to use for DVF dataset?

Elasticsearch provides many field data types and here are some of them used by DVF.

| Field Name | Data Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| id_mutation | keyword | The identifier of the mutation. We can use keyword in Elasticsearch because it can be used for structured content such as IDs, email addresses, hostnames, status code, zip codes, or tags. |

| date_mutation | date | The date of the mutation is stored in the format “yyyy-MM-dd” in the CSV file. This matches what Elasticsearch wanted as well, where the input can be a string containing the formatted date. We can use a date field for queries, such as range query, or for aggregations, such as date histogram aggregation. |

| lot1_surface_carrez | double | The surface in m² for lot 1. Use double because this is not always an integer. |

| nombre_lots | integer | The number of lots. |

| location | geo_point | The latitude and longitude of a given geo-point. It refers to two fields in the CSV file, but after a tranformation in Java models, they are converted into a nested Java class called Location which contains 2 fields: lon and lat, as required by Elasticsearch. This nested object matches the JSON property location. Using this type, we will be able to find transactions within a certain distance of a central point, aggregate documents geographically or by distance from a central point, sort documents by distance, and much more. |

Once we understand which types to use for DVF, the next step is to create the mappings. There are several ways to do this: we can use dynamic mappings or explicit mappings. Since we know all the types, we are going to create the mappings when we create the index. Here, we are going to create an index called “transactions” which will contain all the transactions available in DVF.

Before writing Java code, let’s take a look at how the PUT mappings request looks like in HTTP request and try to get some inspiration for the Java part:

PUT /transactions

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"id_mutation": { "type": "keyword" },

"date_mutation": { "type": "date" },

"lot1_surface_carrez": { "type": "double" },

"nombre_lots": { "type": "integer" },

"location": { "type": "geo_point" },

...

}

}

}

Now, let’s check the Java code:

public static Map<String, Object> esMappings() {

Map<String, Object> mappings = new HashMap<>();

mappings.put("mutation_id", Map.of("type", "keyword"));

...

return Map.of("properties", Map.copyOf(mappings));

}

var request = new CreateIndexRequest(Transaction.INDEX_NAME).mapping(Transaction.esMappings());

CreateIndexResponse response;

try {

response = client.indices().create(request, RequestOptions.DEFAULT);

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Failed to create index " + Transaction.INDEX_NAME, e);

}

if (!response.isAcknowledged()) {

throw new IllegalStateException(

"Failed to create index " + Transaction.INDEX_NAME + ": response was not acknowledged");

}

logger.info("Creation of index {} is acknowledged", Transaction.INDEX_NAME);

In the code snippet above, we provide all the mappings as Map<String, Object>

returned by Transaction#esMappings(), which matches the JSON structure

mentioned above in the HTTP PUT request. The mapping is provided as part of the

index creation request for index transactions. From the Java High Level REST

client client, we call its sub-client index-client to handle the request. To

simplify the demo, I throw an exception when the index failed to be created or

when the response is not acknowledged. In production, I believe we need

something more serious: in case of failure, we probably need to retry the

creation until the destination exists and provide information (metrics, logs) to

improve the observability.

Create New Documents

Now, it’s time to index new documents in Elasticsearch. This can be done using the Index API, where “transactions” is the name of the target index used during these document creations:

PUT /transactions/_doc/<_id>

POST /transactions/_doc/

If we translate the HTTP request into Java code, it can be done in follows:

var json = objectMapper.writeValueAsString(transaction);

var request = new IndexRequest("transactions").source(json, XContentType.JSON);

var response = client.index(request, RequestOptions.DEFAULT);

Let’s take a deeper look at the code snippet above. At the first step, we

serialize the transaction object into a JSON string. This is the source for the

Elasticsearch document. Then, we create an index request for index

“transactions” with this source JSON. Finally, we submit an index request via

Java High Level REST Client client to Elasticsearch synchronously and wait

until the acknowledgment from Elasticsearch. In the code snippet above, we

skipped the exception-handling part to simplify the reasoning because it’s not

the goal of this article. But in production, you will need to be very careful

about this part because it can lead to data loss.

Now going back to the indexing part, once the indexing is started, you can use

the _cat index API to retrieve the list of indices and see a new index

appeared. It’s “transactions” that we just created:

$ curl localhost:9200/_cat/indices

yellow open transactions n4kNyGceQZOhQ0n-Yd8Qgg 1 1 10000 0 3mb 3mb

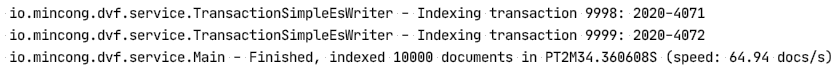

The code above works but it’s far from ideal. It’s too slow. The DVF dataset contains 827,105 records (6-months) and it will take a long time to complete the indexing process. I did a small calculation: by indexing 10,000 documents, we need 2m34, where the indexing speed is 64.94 documents/s (see screenshot below). Therefore, we will need 12,736 seconds or 3.5 hours to complete the indexing process.

🐢 This is not fast enough. In the following article, I will share how to improve this indexing process. At this point, we can consider that the basic indexing process works, and therefore, we are approaching the end of this article.

Going Further

How to go further from here?

- To learn more about DVF, visit the website: https://cadastre.data.gouv.fr/dvf

- To learn more about Elasticsearch installation with Docker, visit the official documentation: https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/elasticsearch/reference/7.x/docker.html

- To learn more about Java High Level REST Client, visit the website: https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/elasticsearch/client/java-rest/7.x/java-rest-high.html

- To learn more about Java framework Immutables, visit the website: https://immutables.github.io/

You can also find the source code of this project on GitHub under project mincong-h/learning-elasticsearch.

Conclusion

In this article, we saw how to download the open data “Demande de valeurs foncières (DVF)” 🇫🇷 ; how to read the dataset using Jackson Data-Format CSV; how to set up Elasticsearch single-node cluster using Docker image; how to set up Java High Level REST Client; how to choose the right data types of the index mappings, such as keyword, date, integer, and geo-point. We finished the operations by creating new documents in Elasticsearch using the simple Index API. However, we also observed that the performance is not optimal and there is room for improvements — which will be discussed in the next article. Interested to know more? You can subscribe to the feed of my blog, follow me on Twitter or GitHub. Hope you enjoy this article, see you the next time!

References

- Etalab, “Base « Demande de valeurs foncières »”, 2020. https://cadastre.data.gouv.fr/dvf

- Tatu Saloranta et al., “Jackson Data-Formats Text”, 2020. https://github.com/FasterXML/jackson-dataformats-text

- Elasticsearch, “Elasticsearch Reference 7.x”, 2020. https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/elasticsearch/reference/7.x/index.html